Wili

Chapter Five

Hope springs eternal in the human breast; Man never Is, but always To be blest: The soul, uneasy and confin'd from home, Rests and expatiates in a life to come. -Alexander Pope, An Essay on Man, Epistle I, 1733 |

The late 1860s and early 1870s was a difficult time for America. The Civil War was over but the wounds were far from healed. The job of "binding up the nations wounds" was to take many decades, if, indeed, it were ever to be accomplished. President Lincoln's words at Gettysburg were seen as noble but not operational. Factional political, sectarian and racial bickering pervaded society. Renegade bands of former Confederate cavalry units plundered and terrorized the Kansas and Nebraska area just as unauthorized "militia" of former Union cavalry units roamed that same area burning out and lynching real or suspected southern sympathizers.

Returning veterans with broken bodies begged on street corners in both the north and the south. Carpetbaggers defrauded the south and hate groups terrorized Negroes. A President was murdered and another was impeached. There was no national euphoria. In the north there were the incongruities of victory and in the south the misery and hatred of defeat. And in both the north and the south, there were the John Reids - men whose bodies remained whole but whose lives lay in tatters.

Native Americans along the Canadian border and in the Arizona territory struggled to retain their lands and culture but were herded into smaller and smaller areas of useless earth. Those who resisted were summarily slaughtered. Reasonable pacification (i.e., all their land had been stolen) of the Plains Indians had occurred but overall, it was not the most shining hour in United States history.

But in one of the few small Indian villages remaining in Kansas, a ten-year-old boy who had more reason than most to be miserable, was instead exceedingly happy. Wili Fox (he was an Indian now. Someday, if he felt like it, he might be Wili Slatz and German again.) personified but paraphrased Pope's thesis. In Wili, joy sprang eternal and to some extent the boy put the lie to Pope. His joy was not in some 'life to come'. It had arrived. It filled him now. His boyish joy was unbounded and it was ubiquitous. It would be the Wilis of the time that would ultimately restore some vigor to the nation.

The experiences of Wili's toddler-hood had permeated his being. Joy was who he was. Running meant happiness to Wili and was as much a part of him as breathing. Unfettered from clothing was his preferred state and he was living in a culture in which the former was esteemed and the latter the status quo. These rudiments of his ego, suppressed and punished in his former life, brought him status and identity in his present life. Wili seemed to know what Carl Jung was to postulate: clothing was a symbol of the artificial. It disguised and hid the real self. While Jung's portrayal of nudity as genuineness was theoretical, Wili's was real. While he and his now many Indian friends worked and played in the only the covering with which they were born, the covering that God or nature had provided them, the boy felt really alive. He was really Wili Fox, not some invention of a repressed society - always wallowing in the mire of confusion, never able to reconcile human nature with the ambiguously preached demands of some ethereal God. For Wili nudity was reality and running was joy and he could now experience both in the ultimate reality - the world as God had made it - undisturbed by buildings, roads, factories, mills, even cooper's shops, and the plethora of conflicting mores - only the company of good companions and the caress of Mother Earth. This was the place and this was the life God had intended for Wili Fox or Slatz - whoever he chose to be at the moment.

But, Wili was a boy and he was ten years old. No ten-year-old boy is a saint and Wili was, indeed, the archetype of the ten-year-old. He fussed with his mama about chores he preferred not to do at the moment. He did not always return home when told, and he balked at certain decorums of his new life that just didn't make sense to him or that the boy in him just felt, at the time, it necessary to resist. Even good, joyous, intelligent, happy boys have the sine qua non of the gender. They are occasionally obstreperous. Wili was indeed all boy.

A part of the decorum of his old life, however, he willingly shed. Wili was not particularly belligerent but if he were hurt or otherwise offended in play, he fought. But, in his present culture, that was not a fault. Boys fighting among themselves was not something in which Indian parents involved themselves. Traditionally, willingness to fight was seen as a mark of honor in boys, not something to be rebuked. In their warring past, Indian boys needed to learn to fight. They needed to learn that there was honor even in being defeated. Staying in the fight brought honor regardless of the outcome. Wili's Indians had not moved so far into white culture that they forsook that notion.

Running away from a fight was the disgrace. Boys who consistently ran from a fight in years past would have been dressed as girls and given girls chores and literally lived as women throughout their lives. Some with a particular disposition as boys satisfied both curiosity and cravings with other boys - boys who may or may not also satisfy those curiosity and cravings with girls. Learning sexual skills was considered as important to most of the world's native cultures as learning any other of life's skills. Experimentation was not only permitted but encouraged and the gender of the partner was of no significance.

As adults, some boys who had lived the feminine life assumed the passive role with a brave whose proclivities were so inclined. There was no derision. Such men were, in fact, held in high esteem. Warriors who were inclined toward both women and men were thought to have a special relationship with the spirits and those who were not warriors, frequently became shaman - medicine men. Those who had lived as women were never to become warriors. But, by the 1870s, warriors were as passé as the bow and arrow and the white man's taboos were beginning to impact Arapaho thought so now such boys were merely teased as boys do each other but they had not yet become pariahs.

Wili also learned that a fight did not mean an extended period of alienation. When he and Vaasco had gotten into a fight, it was at least a week before the vexation dissipated. But now that he was an Indian, fighting was part of friendship. There was momentary anger - or was it just the emotion of fierce competition? - but never distain. In fact, Wili's most frequent adversary was Flying Hawk, his best friend.

Wili had maintained the stout, firm body of his toddler-hood. He was taller and stouter than even the boys of twelve and thirteen summers. When a boy's body began to take on the qualities of manhood, they wore at least a breechcloth and stopped mingling with the boys of smooth skin. That usually happened when a boy was in his fourteenth summer. Actually, as their fathers began to experience more affluence in the cattle business, the clothing of choice for adolescent boys was Levis, those tough, canvas like britches developed for the California miners. Traditional buckskins, however, were still highly prized but, with the scarcity of game, difficult to obtain, and worn only on ceremonial occasions.

But Wili and Flying Hawk, still not encumbered by clothing, were a good match for each other. Flying Hawk was eleven summers but a big boy, almost Wili's size and he was strong. If they fought, Wili still usually won but Flying Hawk gave him the fiercest competition and therefore was the most admired. Indian fights fascinated Wili. He realized that while he was fighting he was not angry as he had been when he fought with Vaasco or the other boys in New Bedford. Indian fights hurt as much but they were more ritualistic than emotional and you felt admiration for your opponent rather than rancor.

Wili was now Indian in every sense. Even his German paleness had been painted tan/bronze by the summer sun. His black hair, though not as course, added to his Indian visage. Only his Teutonic face betrayed his heritage. But Wili's thoughts and values were now Arapaho and he respected what the Arapaho respected. Bravery and tenacity were virtues and Flying Hawk was well endowed with both. Flying Hawk had earned Wili's respect but they just liked each other. Wili had learned early that one can like many people but only a very few are just right for you. Vaasco was one of those. Flying Hawk was another. Wili and Flying Hawk were just right for each other.

And, they found they had some games in common. Lacrosse played in New England was not the version played on the prairie but the rudiments were the same. Wili had brought with him from New Bedford a commercial stick. The style and workmanship of the stick were soon duplicated by the native skill of his friends' fathers. Games were rough and boys sported bruises, black eyes and frequently lost blood but it was fun and even the adults enjoyed watching and the men and adolescent boys were soon organizing games of their own.

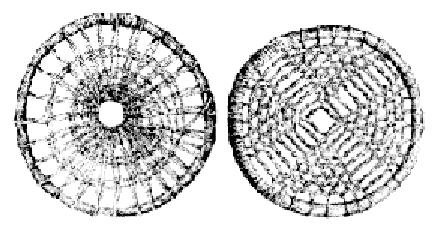

Not all play was organized. The hoop and lance were still the favorites of most boys. The hoop was interlaced with rawhide with openings no more than three or four inches square. It took impeccable timing and an accurate arm to throw the lance through the rolling hoop. Hitting the center hole gave the highest score.

Wili's New Bedford games had also caught on. The spinning top was gaining popularity as was rolling the barrel hoop. Wrestling and foot races (which Wili always won) as well as frolicking in the river consumed much boy time. Wili never did win at hoop and lance, however. That game took more skill than Wili had had time to develop.1

But, what Wili enjoyed most was the Plains Indian boys' version of cowboy's and Indians. It was played on real horses not as in New Bedford with a dragging stick between your legs and a silly galloping gate with your feet. The game included mostly riding fast, chasing each other and whooping their childish versions of war cries. Occasionally Wili had to be the cowboy and he had long ago lost track of how many times he had been scalped but it wasn't his whiteness that made him the cowboy. It was just his turn. It was not only Wili who saw himself an Indian. As far as all the boys were concerned, Wili was an Indian. Being an Indian was the right thing for Wili right now. He thought of his first mama and papa occasionally but it was now with love more than sadness. They had loved him and he them but they were gone, the ray of light in a very dark past. Wili now lived in a bright present that allowed him to relish that light and ignore the former darkness.

Wili loved to sit around the campfire at night and listen to the old men tell stories. He didn't understand a word for the first several months but this was a really Indian thing to do. His Papa told him that it is what Indians had done since there were Indians. If Wili didn't fall asleep and have to be carried home by his Papa, he could sometimes get his Papa to tell him the story in English. The stories were exciting. They were of buffalo hunts, of savage winters, of prairie fires, of raiding parties, of how the Great Spirit created the Arapaho, of great chiefs and brave warriors. These were real Indian stories. Not the kind he had read from books in New Bedford. Wili loved being an Indian.

If Wili was well respected by his playmates, he was worshiped by his sisters. It may have been that males were still seen as being of more value than females in Indian culture but it was probably Wili's blithe self that so animated his sisters. They now had a brother and not just any brother. He had become the admired leader of his peer group. His mien had even gained the grudging regard of most of those elders who still held residual hatred for the white man. Among several of the older braves, Sand Creek was still too much with them.

Wili would brook no derision of his sisters. The Indian's traditional view of the female as of less value than the male was totally alien to Wili. He was still too much a child in his white past to have known that much the same attitude existed there. So, expression of such a point-of-view had frequently made an age-mate the beneficiary of Wili's ire and his fist. No one was going to speak derisively of his sisters. So subjugation of women had long been an Arapaho tradition. Everyone in the camp was saying that they were moving toward the white man's world. Wili was white and he had never heard of such a thing. In his way of thinking, girls and boys were people - the same.

That is not to say that Wili did not have the typical ten-year-old aversion to girls but there is a difference between girls and sisters. Wili would tolerate an occasional derogatory remark about a girl or even girls in general but never about his sisters. This village was moving toward the ways of the whites. It was generally understood that it would take time to understand and accept all the ways of the whites. Maybe, but not where Wili's sisters were concerned. Children and adults quickly learned to be very discrete when referring to the Fox girls.

Wili had, at first, thought that Sadie would be his favorite. Sadie was a baby and he had loved Wina so when she was a tiny baby. Within days, however, Wili realized that he had no favorite. Each of the girls had her qualities. Ruth was very bright and very curious. She was so much like her mother. But so far as Wili was concerned, she had only one major quality. She adored him. Wili had been loved by his parents but that was just the way things were. Parents love their children. Wili had had no siblings other that Wina and while Wina had cooed and giggled when Wili played with her, her ability to express deeper feelings was limited by her age. But Ruth was six. She would follow Wili around. She needed to touch him. She tried everything her six years had taught her to make her brother happy. Wili found it a very heady experience to be so obviously adored.

Mary was just plain cute as only a three year old can be. Toddlers are, perhaps, at the cutest stage of childhood and Mary made the most of hers. She was too young to determine if she had inherited her mother's intellect but she had certainly inherited her sense of humor. Mary was funny and she knew it but was not obnoxious about it. Wili loved all of her but the thing he enjoyed most was that Mary loved to be held and cuddled.

And Sadie - she was such a happy baby. When she saw Wili, if she was in her mother's arms, she squirmed and wiggled and reached until Wili took her. How could he not defend his sisters if he was the center of their worlds - sometimes, it seemed, even more than their mother.

Was it some strange primitive magic that had run with Wili that first day? Had some shaman ritual obliterated Wili's past. Wili had known loss, he had known cruelty and derision, and he had seen horror. He should have been a sad, frightened, lachrymose child. But he was jubilant. He was robust. He was joy. He was happiness and what he was, was infectious. His simple presence made other people happy. Had that run been as much spiritual as physical? Had he really run from one world to another? It didn't really matter how it happened. Wili Fox was one happy little Indian.

Abraham Fox didn't know how it happened either. He didn't know whether to do some kind of homage to the Great Spirit or to thank the God of the white man. He had wanted a son but he could never have imagined the son he got. Abraham saw all the things that made Wili so popular in the village and he was proud of his boy. But he now had what every man, regardless of ethnicity yearns for: the love and respect of a son. And Wili did love his Papa. He had loved Papa Dieter but Papa Dieter was gone most of the time. Papa Dieter was part of a world that took families apart. It took papas to work where boys could not go. It was a world where boys had to wait until they were "old enough" to learn what Papas do all day and old enough to be of any real productive value. Wili knew he was loved and for what he knew then, that was enough.

But Papa Abraham could and did take Wili with him when he worked. He could teach now what he knew and what he wanted his son to know. Wili was big enough to do things of importance. He could help his Papa - not only by fetching water and gathering fuel but help with the things his Papa did. He felt part of his Papa's work. He saw the pride and appreciation in his papa and he knew now that love was not the only thing a child must have to thrive. Being needed, contributing to the things that sustained the family completed the circle of the soul. Loving, being loved, contributing - that was the circle of wholeness. Wili Fox was not only a happy boy. He was a whole boy and he would be a whole man. Could he have become that in New Bedford? Maybe but it would have been a different kind of wholeness. If Wili had never become an Indian, perhaps that kind of wholeness would have been enough. But Wili was an Indian. He had learned to live intimately with Mother Earth. He had learned her wholeness and he just knew that he would never be satisfied with any other.

Wili pondered the different love of is two Papas. Wili never doubted Papa Dieter's love and he knew that, after his mama died, he was the most important thing in his Papa's life. But, with Papa Dieter, Wili was a boy and Dieter was a man. There was like a wall of something between them. Maybe it was time. They weren't exactly parts of the same world. Wili was still a boy but Papa Abraham seemed to see the potential man in him and he related to and nurtured that man. It was a kind of friendship as well as a father and son relationship. Maybe it was because Wili was getting older but it was probably because in New Bedford, schools were for teaching. Papas were for loving. With Indians Papas were for both. How do you explain a feeling like that when you are only ten years old? Wili didn't love Dieter less. But it was a different time and place and his love for Papa Abraham was the right love for Wili now.

Summers can be very hot in Kansas. In the several months that Wili had been an Indian, there had never been a reason for him to wear clothes. It was a handy way to live. If the day's play was in the river, wet clothing was a hindrance: too heavy and a collector of mud. The same was true for play in the rain. The slight breeze that always seemed to be present could blow over the bare skin and more quickly evaporate the perspiration and cool the body. To Wili, who knew some of two cultures, this was by far the more sensible way to live.

He was, therefore, more than a little surprised and a little irritated when his mama took him to the river and thoroughly bathed him, inspecting every possible fold in his skin that might hide some impurity. Wili protested loudly but Fern said nothing but gave firm indication that she would not be dissuaded. She was going to give the boy a thorough bath.

She took him back to the tepee and anointed his entire body with what appeared to be a very light oil. Actually, it was cattle fat rendered and purified according to the ancient Arapaho tradition. It was so pure that it had no odor and, if properly stored, would not become rancid for years. Before the sacred buffalo went, it would have been buffalo fat but even sacred ritual had to adjust.

Wili's hair now reached almost to the middle of his back. His mama applied some of the sacred "oil" to his hair and braided it. The braids fell over his shoulders almost to his elbows and the lightly oiled blackness glistened in the sunlight. Wili thought they looked good but still wasn't sure what was going on. His mama had not said a word to him since she had taken his arm and pulled him gently to the river.

Wili had seen his mama working on something buckskin but had no idea what until he was dressed in what had to be the finest buckskin breeches and jacket ever. It had bead work on the chest and the back and fringes on the sleeves and down the sides of the pant legs. The moccasins were beaded and tufted. Wili had never been a connoisseur of clothing but he knew that at this moment there was probably no one more finely attired than he in the entire world.

His mama, still silent, led him out of the tepee. Abraham was just exiting the cabin also wearing very handsome buckskins. He signaled that Wili should not speak and motioned the boy to follow him.

Wili followed his Papa toward the center of the village, the place where he had listened to stories around the camp fire. He saw other braves and their sons, dressed as he was and as silent and somber as Wili was sure he had to be. He didn't know what was going on but he got the idea that it was something very important - maybe even sacred.

He saw Flying Hawk. His first impulse was to greet him as he did when playing but the look in flying Hawk's eyes told Wili not to.

Tall Man was there with Echo and Keechee the medicine man. Tall Man said something in Indian and Keechee began to dance and chant a funny (to Wili) yipping and wailing kind of song. When the song was done, all the braves formed a circle, Abraham beside the Chief and Flying Hawk's papa, Lone Hawk beside Keechee. Each brave that had a son at least Wili's age, sat in a circle and pulled his son down in front of him.

Tall man spoke. "Men of the White Buffalo Calf Clan of the Arapaho, we are now in the sacred council. The spirits have not told us in the thunder that this is a bad time to think. We must think of several things. Keechee has asked the Great Spirit to wash our minds so that our thoughts will be wise and fair.

"Red Fox comes with a petition..."

"Why do we play this game? He thinks that he is no longer Arapaho. He calls himself Abraham as if he were a white man - a white man like those who stole our land and killed our buffalo." Broken Bough was very old and very bitter. His squaw and his children had been massacred at Sand Creek.2 He stayed with Tall Man because he had always been of the White Buffalo Calf Clan but he did not think as did Tall Man. He did not think like those who had gone south to Indian Country. To Broken Bough there was no honor left among the Arapaho. If there were any honor left among the Arapaho, they all would have died fighting and killing white men.

"We know that your heart was emptied at Sand Creek, Broken Bough. Many hearts were emptied there. None have understood why the Great Spirit has abandoned us. All of us are sad. Empty hearts can be filled with hope or hatred. Most of us here have chosen hope. You, Broken Bough, have chosen hatred. You are an old man and must be honored. We do honor you but not the hatred in your heart.

"You are a brave of the White Buffalo Calf Clan but are not the only one. We are all braves of the White Buffalo Calf Clan. All here have the right to speak and not all empty hearts have been filled with hatred. You have the right to speak in the council but those who speak must also listen. We do not play a game. We do not live as we once did but we must live. These boys do not know the old ways and they will not learn them. The old ways are of no use to them. But they are still our sons and we must teach them. It is hard to teach when one does not know what he is teaching. We do not know what our lives will be as our fathers' did. It is foolish to teach what they did. What they knew no longer is. What we must know we do not yet know. It is hard to teach what we do not know so we will not try. Since we can't teach what we do not know, we must teach hope.

"Sons of braves, hear me. Broken Bough was a brave warrior. He brought honor to our clan and you must honor him. But he is old. His heart is old. It cannot become new as our lives must become new. You must honor Broken Bough because he is old. If you are to live, you must never let your hearts become as his."

Tall Man again looked at Abraham. "Speak your petition, Abraham."

"I have three daughters. I now also have a son but he is now only the son of my heart, not of my clan. We are living in a new time. I could ask the white man's judge to make him my son. He probably would not do that. But he is in my heart. He is in Fern's heart. He is in the hearts of my daughters. He has made us very happy. We had good hearts before but he has given us new, even better hearts.

"I know the old ways are gone but I honor them. I petition the council to make the son of my heart the son of my clan."

"He is white!" Broken Bough's voice was full of venom.

"Do you remember what that devil Chivington said when asked why he slaughtered our children at Sand Creek. I remember what he said. While I was looking at my dead children he said, 'Nits make lice'. My dead children were nothing to him. They were no more than a bug to be squashed. If an Indian child is a nit, then all children are nits. If this council allows that white nit to be part of the White Buffalo Calf Clan, I would rather die than see my clan defiled."

"Colonel Chivington was an evil man. Most white men I know say he was evil. Sand Creek was evil but what is gained by living on evil. In the old times we fought and killed Indians of other tribes because we thought they were evil. They thought we were evil. We lived on evil and what did it get us?

"You are an old man, Broken Bough so I will forgive you for calling my son a nit. I am ashamed that one of the White Buffalo Calf Clan would be like Colonel Chivington. I will forgive, Broken Bough, but I will not forget. Should any harm come to my son at your hand, I will forget that you are old."

"I will do him no harm but I will hate him. I have no squaw. I have no children. I have not many years left. I will always have only what I have now and I have only hate. I will keep it. I must have something."

"Hate if you must, Broken Bough, but you will be robbing yourself. The son of my heart is strong, he runs fast and he learns quickly. He is a boy but he is wise and he is joy. He is so much joy that he gives joy to those around him. He is in the hearts of many in this clan and those hearts know the joy. Hate if you will but there is joy here. You could know that if you would.

"The son of my heart has known sadness. The mother who gave him birth died and he had to watch his white father die. He has told me that he wanted to be sad. He wanted to be angry. He did not know hate but if he had, he would have wanted to hate. But, he told me, something in him, perhaps the Great Spirit or the God of the white man, told him to run. So he ran and as he ran he ran away from the bad to the good - perhaps, Broken Bough, from hate to joy.

"He is a boy. He must not speak at the council. Boys come to the council to learn, not to speak. But if he could speak, he could tell you how to run from hate to joy."

"There is no joy. It all died at Sand Creek." Broken Bough stayed in the circle but he turned his back to the chief. He would not leave the clan but he no longer wished to be part of this council.

"Wili Fox will be my son. If this council will make him one of us, he will also be New Heart. I revere the old ways. When I think of them, I am Red Fox and I am both happy and sad. But I know that I live in the new ways. In the new ways I am Abraham Fox. I beg the council to allow the son of my heart to be both Wili Fox and New Heart. I have spoken."

Each member of the council could speak if he wished. They started at Tall Man's left and would work around the circle. If they approved they would place the pointed end of their council stick toward the middle of the circle. If they disapproved, the pointed end pointed toward the outside the circle. Keechee spoke first.

"The White Buffalo Calf Clan has always honored the Great Spirit. We learned our ways when our fathers were Cheyenne. After many years the Arapaho began to live apart. We followed the buffalo to different places than our brothers the Cheyenne. We became a different people but we have never been enemies of the Cheyenne. They are our brothers. We have fought by their side. We have died with them at Sand Creek. We are The People. If Red Fox wants a son, let him adopt a Cheyenne boy. It has been only six summers since Sand Creek. There are many Cheyenne boys whose fathers died fighting at Sand Creek and whose mothers were slaughtered in their sleep. Let me say again, if Red Fox wants a son, let him adopt a Cheyenne boy. The Cheyenne know the spirit dances. A Cheyenne boy will honor the Great Spirit. I have spoken."

Keechee placed his stick point outward.

Tall Chief glanced at Abraham giving him permission to respond.

"The Cheyenne are in Montana or in Indian Territory. New Heart is here. Why would I look among the Cheyenne when I already have a son in my heart? How can the Cheyenne boys know the spirit dances when Keechee says all their fathers are dead? Keechee talks with two tongues. New Heart will be my son. I have spoken."

Lone Hawk spoke. "New Heart is a good name for Red Fox's son. He has given my son a new heart. He has given me a new heart. I will be proud when New Heart is a member of the White Buffalo Calf Clan."

Loan Hawk placed his stick point toward the center.

The next several braves chose not to speak but each placed his stick, point toward the center.

Black Buck had wanted Grey Fern to be his squaw. Her father had chosen Red Fox. Although they had not fought, the clan knew that Black Buck's blood was bad for Red Fox.

"We are a poor people. We find it hard to feed our children. The whites have taken our land and killed our buffalo. Many Indian children have starved. The whites do not care for Indian children. Why should The White Buffalo Calf Clan care about a white boy? Let the whites feed him. I want the food we have to feed Indians."

Black Buck placed his stick point outward.

Abraham spoke. "I have asked you to help me with my cattle. I have told you that I will pay you. You have chosen to pretend that we are still in the old times. You try to hunt when there is nothing to hunt. If your children are hungry it is because you are foolish."

"How can I work for you when our blood is bad for each other?"

"I have no bad blood for you. Fern's father was free to choose. He chose me. You have a fine wife and she has given you fine children. Perhaps Fern's father chose me because he saw that you are foolish. If your children are hungry, send them to my tepee. Fern and I will feed them and they will know that their father is foolish. Is that what you want? Do you want your children to know their father is foolish? If you come to my teepee before I ride to my herd in the morning, I will give you work. We were friends as boys. You were not foolish then. My blood is not bad for you. It would make me happy if we could be friends again.

"Think, Black Buck, if I were to die, would you leave your wife and children and come to Fern's tepee. I don't think so. You have what you have and I have what I have. I can see that you are happy with what you have. I am happy for you. Ten years is too long to hold bad blood. Come to my tepee in the morning."

The remaining council members all pointed their sticks toward the middle. Tall Man stood to welcome New Heart into the clan. "The council has spoken. Only two...."

A murmur in the area where Black Buck was sitting drew Tall Man's attention. Black buck had turned his stick around. It now pointed toward the middle. "The Council has spoken. Only one has objected.

"Come Red Fox. Bring your son."

Abraham and Wili stood before Tall Man. With his medicine bundle, Tall Man touched Wili on the head. "Think wise thoughts."

He touched each shoulder. "Bear heavy burdens."

He touched each arm. "Do strong deeds."

He touched his hands. "Hold tight to truth."

He touched his heart. "Love honor."

He touched his genital area. "Father wise children."

He touched his legs. "Walk the path of peace."

He touched his feet. "Stay firmly planted in justice.

"You are now New Heart, son of the Clan of the White Buffalo Calf. If you do these things you will bring honor to your father, to your Clan and to yourself."

Wili wanted to hug his Papa but he didn't know the rules of the council. Only the men had talked and only when Tall Man said they could. Wili looked at Tall Man and then at his Papa. With a nod, Tall Man gave him permission. Wili leapt into his Papa's arms. The council became much less dignified. There were yeps, yelps and even Keechee was dancing and singing. He had had his say but he had lost. He bore no ill will. This was a time for celebration so everyone celebrated. Everyone, that is except Broken Bough. He said nothing and he did not move. When Wili woke the next morning, Broken Bough was still sitting in the same spot.

1Additional information regarding games played by plains Indian children found on Native American Technology and Art web site - http://www.nativetech.org/

|

|

Other Native American Games & Toys

Lacrosse - ball game played on a field between goal posts with a ball and a racket of a three foot sapling, the end bent into a circular hoop and filled with a leather network.

Moccasin Game - guessing game where an opponent has top guess which moccasin an object is hidden in. Beans or markers are used to keep score.

Hand Game - guessing game where an opponent has to guess which hand an object is hidden in. Sticks and markers are used in scoring.

Double Ball - played only by women and resembling lacrosse - suing two balls or sticks connected with a thong and each woman equipped with a stick.

Awl Game - a hoop from the leg bone of an animal was set out on the ground and an awl was thrown toward it, intending to stand upright in the ring.

Snow Snake - played in winter by men on frozen lakes using a carved stick a meter long, with a head resembling a snake. The snow snake, thrown on the run, races along the top of the ice, the farthest traveled being the winner. The track, pressed down into the snow with a log, could be a mile long.

Web Weaving - (like cat's cradle), played by children and adults using a long string tied in a loop to finger weave patterns of animals, tipi doors, and other designs like 'fish spear', 'bird's foot', and 'crow's nest'.

Sling Stick - Sling sticks about 2 feet long with a notch and a thong attached at one end. A stone is placed in the notch. The thong keeps the stone in place and is held down with the thumb by a loop at the other end of the thong. The stone is thrown great distance when the stick is whipped forward - releasing the thong and the stone.

Little Sticks - (like jack straws), drop from your hand a bundle of thin cedar sticks, two players try in turn to remove sticks from the tangled heap without moving any of the others. A basket splint is sometime used to pick up the sticks.

Top Spinning - a disk of bone, stone, or wood with a peg through it, sometimes painted or decorated on the upper surface, for divination of personal questions like 'who will marry first', etc. by spinning the top and seeing who it points to when it stops. Sometimes tops would be whipped with a stick to keep them in motion.

Marbles - made from fir balsam pitch or stones were either rolled down a board to see who's could go the farthest, or they may have been rolled into a series of holes about the size of the marbles.

2See www.lastoftheindependents.com/sandcreek.htm